Dramatic spike in emergency removals of children by ACS

It all began with two high-profile child deaths in 2016.

Emergency removals by the New York City Administration for Children's Services Center for New York City Affairs

A new report finds a dramatic increase in the number of emergency removals of children by the New York City Administration for Children’s Services.

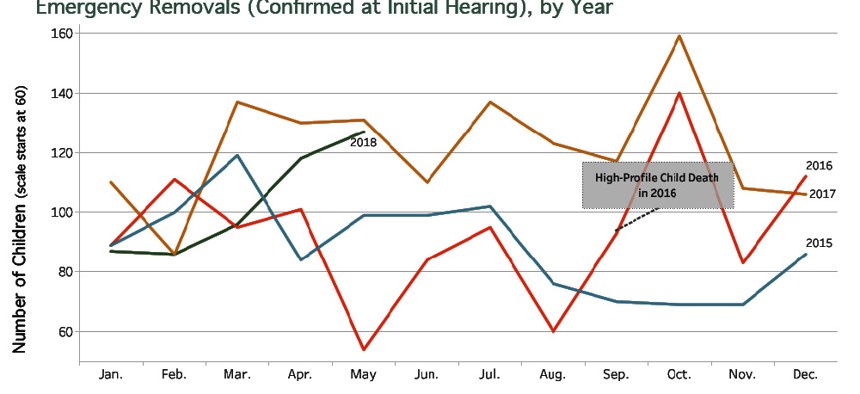

Agency records show that 2,303 emergency removals – which are removals when a child is taken from a home before the case is brought to a family court judge – happened between Oct. 2016 and May 2018. That number represents an approximately 30 percent increase compared to the previous 20-month period, according to the report from The New School’s Center for New York City Affairs.

The jump follows a historical pattern where high-profile deaths lead to more strain on the system as calls from anxious members of the public increase and caseworkers become more aggressive for fear of losing another child in a dangerous situation. Family courts have swelled to a “new level of dysfunction,” the report says, yet the total number of children actually placed in foster care remains near record lows.

“Observers inside and outside ACS say the surge of cases is driven by heightened anxiety and caution – both among members of the public, who are calling in more reports of possible child abuse and neglect, and among child welfare staff, who are responding to those reports more aggressively,” reads the report.

The surge in emergency removals began in October 2016 – around the same time as the deaths of six-year-old Zymere Perkins and three-year-old Jaden Jordan. The deaths led to the resignation of Gladys Carrión as commissioner of the agency. David Hansell was appointed commissioner in February of 2017.

“Take the case to court and let the judge say no (to an emergency removal). Then we can document we tried ... Nobody wants to end up with their face in the Daily News. They don’t want to face criminal charges.” – Anonymous ACS caseworker.

Caseloads spiked to nearly 14 per child protective worker from 11.6 three years ago – nearly double what a proper caseload would be. And bringing on hundreds of new employees is only a partial solution given the historically high rates of staff attrition within the agency, according to Ronald Richter, a former ACS commissioner quoted in the report.

Just how many of those cases leads to emergency removals remains a mystery, because the agency only discloses data on removals that received court sanction, according to the report. The ACS monthly reports upon which the report is based do not indicate a total number of children removed from their homes by ACS. They also do not tell which children are reunited with families at the initial court hearing or after the judge decides a case after the first day, according to the report.

“At this point everybody’s so afraid, they’d rather cover their ass,” one caseworker who requested anonymity said in the report. “Take the case to court and let the judge say no (to an emergency removal). Then we can document we tried ... Nobody wants to end up with their face in the Daily News. They don’t want to face criminal charges.”

The total number of emergency removals is likely much higher than those upheld in Family Court, Joyce McMillan, director of programming at the Child Welfare Organizing Project, said in a telephone interview.

“I think it’s a lot of cases and that’s why ACS is refusing to capture it in its entirety because it will show their overzealousness,” she added.

An ACS spokeswoman did not say why the agency does not release the number of emergency removals that happen but are not endorsed by a judge at a court hearing. Additional resources and oversight have been allocated to the agency under the tenure of Commissioner David Hansell, Chanel Caraway said in an email.

“Commissioner Hansell has made top-to-bottom improvements at ACS, strengthening our child-protective work and expanding the services we provide to support families,” she said in the email.

McMillan recalled two cases where parents initially refused to cooperate with child welfare investigators who demanded inspections of their homes. The investigators came back with police officers who then stood by as the children were removed from the families – though they were returned soon thereafter.

The agency has filed petitions in Family Court involving nearly 26,000 children in the 20 months after Perkins death. Judges are petitioned to order a family to participate in services such as drug treatment and family therapy, according to the report. The agency can also continue to monitor the family.

Placements in foster care have gone up a slight 4 percent in the 19 months after Perkin’s death. That runs counter to a longtime decline in the foster care population. About 45,000 children were in the foster care system in the mid-1990s, but only about 8,600 are in placement now.

Still, family judges now sometimes have only 10 minutes to hear cases that will determine whether children get to stay with their parents. But they will likely not dismiss a case, according to Richter, who has served as a Family Court judge. They too are anxious about having a child die because a decision they might make, he said in the report.

The system as a whole has over-reacted to the child deaths and that has led to other children getting traumatized when their parents have just a few minutes in the middle of the night to figure out how to react to ACS’ attempt to remove their child, Emma Ketteringham, managing director of the Family Defense Project at The Bronx Defenders, said in the report.

It bears some resemblance to events at the U.S border with Mexico, she told the Center for New York Affairs in the report.

“With all of this attention being paid, nationally, to what removing a child from a parent actually looks and sounds like. It’s no different when a child is removed from a parent here in the Bronx,” she said in the report.