Nations of Immigrants

Last year the deportation cases of tens of thousands of unaccompanied Central American children overwhelmed already backlogged immigration courts around the country. Despite the creation of special surge dockets to process that increased caseload, the majority of legal proceedings in New York are yet to be resolved—with some potentially dragging on for another year. While the number of new arrivals tailed off at the end of last summer, a steady trickle has continued to turn up. Given that migration to the southern border tends to follow seasonal patterns, a larger wave—if not the tsunami seen in 2014—could soon sweep in.

In recent years, New York has made efforts to improve immigrant access to the legal system. Under U.S. law there is no right to appointed counsel in immigration proceedings. An October 2014 study conducted by the TRAC Research Center found that over 80 percent of unaccompanied children immigrants without legal representation were deported while nearly three-quarters of those with representation were allowed to remain in the country.

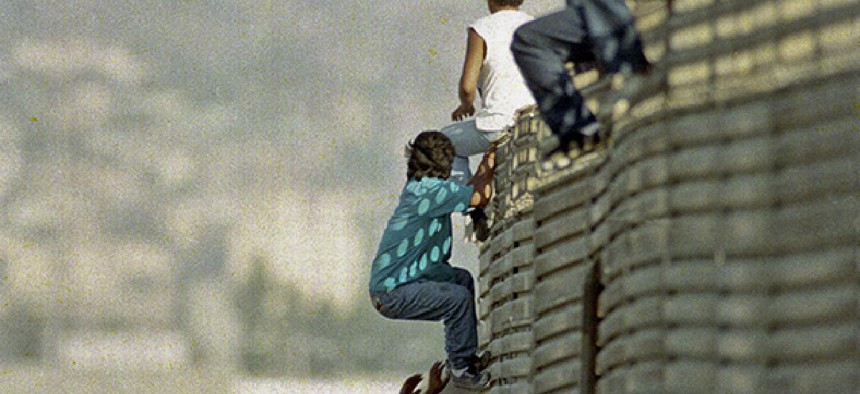

The road to winning the right to remain in the country is a long one, but Central Americans start with one advantage: they are entitled to a hearing before a U.S. judge. Mexican children, in contrast, can be immediately deported. Though some media reports depicted the 2014 surge as a breakdown in border security, most unaccompanied Central Americans “present” themselves to border agents. Their first destination will typically be a detention center run by the Department of Homeland Security, which advocates have long claimed fail to meet acceptable standards in the provision of food and medical care, room temperatures and the overall treatment of detainees.

By law, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) cannot detain unaccompanied minors longer than 72 hours. From DHS facilities the minors are transferred to the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), where they remain in shelters before being transferred again to a private child welfare agency contracted to provide them with shelter for up to 60 days, along with support services such as acculturation lessons, health, education and legal services, case management, individual counseling, and access to recreational and leisure activities. Pending their immigration hearings, the children are held in “the least restrictive setting that is in the best interest of the child.” Since the vast majority of these minors have relatives in the United States, that requirement almost always translates to children being released to sponsors—a parent, relative or family friend.

“What we see are kids showing up with just the clothes on their back—or a few personal belongings they managed to carry with them—often malnourished, scared, wary of trusting others and in need of care,” said Henry Ackerman, chief development officer of Abbott House, one of thirteen private child welfare agencies in New York that provide temporary shelter and transitional services before releasing the juveniles to their sponsors.

Most of the unaccompanied minors emigrate from the “Northern Triangle” countries of Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala, which have among the highest homicide rates in the world. Led by smugglers known as “coyotes,” the minors undertake perilous treks through violence-wracked regions en route to the U.S. border. Along the way, many fall victim to robbery and sexual assault, among other crimes. Some are fleeing gang violence and poverty; others hope to reunite with family members; for most, a combination of push-and-pull is at play.

Many of the kids join relatives—who themselves are sometimes unauthorized to be in the country—facing economic hardship and even housing insecurity in some cases. Since the majority hired smugglers to help them reach the border —whose services routinely cost as much as $10,000— teenagers might be expected to contribute financially to the family. Attempting to work, though, only increases their likelihood of deportation.

The fact that some children have lived apart from their parents for so long complicates the dynamics of reunification. Despite enduring hardship both before and during their cross-border journeys, for many children the more commonplace privations cause the greatest pain. Many have gone through repeated separations and changed caregivers multiple times, with some experiencing abuse along the custodial chain.

The acculturation process alone can cause heightened anxiety and feelings of isolation. Many Central American children additionally demonstrate symptoms of post-traumatic stress and some are reluctant to leave the temporary shelters at which they arrive in New York.

“A child needs a secure attachment to parents or someone who fills that role,” said Dr. Cristina Muñiz de la Peña, the medical health director at Terra Firma, a medical-legal partnership that serves immigrant children in New York.

Most of these minors have two potential pathways to relief from removal: asylum or Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) status. To be granted asylum, a refugee must prove an individualized fear of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular group. And it’s not always clear, for instance, how a violent threat from a gang member fits into those categories. Membership in a particular social group is the protected ground that immigrant attorneys have found most pliable, but more children opt to pursue SIJ status, which can be attained by demonstrating neglect, abandonment or abuse. Pursuing SIJ status typically takes longer than applying for asylum but can also be easier to prove.

In some hearings, the physical scars of violence can be presented as evidence that the asylum seeker fled a specific threat, but outcomes more often hinge on the retelling of facts and events that occurred thousands of miles away. In those cases, the credibility of the individual seeking relief may be the deciding factor.

“It’s extremely difficult—and potentially re-traumatizing—to ask kids to talk about the most dangerous, scary experiences that they’ve been through, and much more so when the consequences of what they say will probably determine whether or not they’re sent back to the situation that scared them,” said Brett Stark, the legal director of Terra Firma. “A lot of kids don’t want to talk about those things, and they’ve avoided thinking about them, and now they’re being asked to recall in detail the very things they’ve been trying to forget.”

“There’s a lot of fear of deportation,” Dr. Muñiz said. “Going to court can be very stressful. Sometimes the kids don’t understand a question, but don’t ask what it means because they’re afraid. Attorneys on the government side ask harsh questions to see if the child is lying.”

A 1982 U.S. Supreme Court decision (Plyler v. Doe) held that states cannot bar students from receiving a free primary and secondary education on the basis of their immigration status. In the United States, even children without immigration papers are required to attend school. In response to the 2014 surge, the de Blasio administration sent representatives to the federal immigration court to assist children with school and healthcare enrollment. On Long Island, there were reports of children being turned away from public schools for failing to produce the proper paperwork. In New York, children under the age of 19 are eligible for state-funded healthcare, Child Health Plus, regardless of their legal status.

“When you meet the kids they seem to be doing fine, going to school, making friends and slowly adapting,” said Dr. Cristina Muñiz de la Peña. “But when you look closer, some have problems paying attention in class, sleeping, acting defiant.” Even those families with health insurance may have trouble finding Spanish-speaking psychologists in their area for the newly arrived minors. Others may fear exposure or come from families that are uninformed about the potential benefits of individual or group therapy.

While New York City attorneys attest to being stretched thin by large caseloads, they believe the fundamental needs of their clients are being met. The New York-based Immigrant Justice Corps became the country’s first fellowship program to provide legal assistance to immigrants in need. In November 2013, the City Council apportioned $500,000 towards providing indigent immigrants with court-appointed deportation defense counsel. The following September, in response to the surge of unaccompanied minors, the City Council—in partnership with the Robin Hood Foundation and the New York Community Trust—allocated $1.9 million toward their legal representation through a coalition of nonprofit providers. This funding targeted approximately 1,000 unaccompanied immigrant children eligible for relief but without the resources to secure legal counsel.

Although a similar $500,000 public-partnership was launched on Long Island this past February, advocates claim the availability of services outside of New York City is much more limited. In fiscal year 2014, nearly 6,000 unaccompanied children were released to sponsors in New York, according to ORR data. More than half ended up in Suffolk and Nassau counties alone.

“The youth on Long Island, Westchester and other counties outside of New York City struggle because, while they have services out there, it’s just not to the extent needed,” said Marika Dias, the managing attorney at Make The Road, one of providers of pro bono legal services in the New York City coalition.

When children go without access to pro bono representation, their families may muster the resources to hire a private attorney to make one or two court appearances, but often cannot afford to see the case through. Some less fortunate families have fallen victim to notaries passing themselves off as attorneys. (In Latin America, “notarios” are qualified to provide legal counsel.)

“Having one attorney with 60 - 80 cases of kids that they have to manage at one time is not ideal, but it’s much better than a 5-year-old going in front of a judge by herself and getting deported, which happens all the time in other states,” Stark said. “We’re very grateful for the partnerships we have in New York.”

In the current fiscal year, 935 unaccompanied minors had arrived as of March, according to ORR. Nassau and Suffolk counties continue to rank among the leading destinations. The cases of juveniles who arrived either before or after the 2014 surge are not eligible for the expedited docket.

“If there’s another surge,” Dias said, “there will have to be a significant increase in funding for pro bono resources to these young people.”

Though it escaped public notice, the first uptick in unaccompanied minors arriving from Central America was recorded in 2012. Through February of the current fiscal year, the number of unaccompanied children apprehended at the southern border was down more than 40 percent from last year (when some 68,000 entered the country), according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. The current pace could result, however, in more than 40,000 entering the country this year, according to the Washington Office on Latin America think tank.

“Looking at the figures through March of this year it’s clear that, if the current pace continues, 2015 will surpass 2012—and it could easily surpass 2013 as well,” said Susan Long, director of the TRAC Research Center at Syracuse University.

Long noted, however, that there is typically a lag between when immigrant children are picked up at the border and when their court papers are filed, so despite there not yet being evidence of it in court data, a fresh wave of immigration could be underway.

Unlike in other legal proceedings, the government is not required to serve the children in-person with notices to appear in court. Failure to show up in court could result in a deportation order. Rather, notices to appear are delivered to the child’s last known address.

NEXT STORY: Data-Driven Solutions