Politics

Four months in, benefits of NY's medical marijuana program outweigh issues for patients

Four months into the state’s fledgling medical marijuana program, and some seizure patients receiving the new medicine are seeing dramatic improvements in their quality of life, and in some cases have begun weaning themselves from often addictive pharmaceuticals they’ve been taking for years. Although the program has struggled out of the gate and is riddled with gaps in service provision and bureaucratic holes, caregivers and patients are expressing great enthusiasm over what they’re seeing firsthand.

Chaffee resident Christina Kelly had long watched anecdotal evidence pour in from other states where medical marijuana was made available. She made sure her daughter’s neurologist was on board from day one, and was among the first caregivers in the state to gain access to the medicine. Her daughter Mariah, a 19-year-old mostly wheelchair-bound woman with a developmental disability and a severe seizure disorder, seized in Wegman’s just hours after Kelly had received their first product. Kelly took her into a private area and administered the first dose. What followed was a reaction and recovery Kelly had never seen after a seizure.

“She slept for an hour, woke up and was ready to take on her day, and not antsy and fidgety and ready to crawl out of her skin, which is how she would have been, typically,” Kelly joyfully reflects. And she didn’t have to spend days recovering from both the seizure and the harsh anti-convulsants. “Cause and effect, I don’t know, but we’ve been dosing ever since that day.”

What that means is that Mariah now takes three doses of a higher CBD to THC ratio (the two main compounds found naturally in marijuana) and higher THC to CBD ratio at bedtime.

“There have been phenomenal changes,” Kelly says. “[Mariah] depends largely on a wheelchair because she’s tired, you know. Her muscles are so stiff and so tight. She’s just so altered from being on pharmaceuticals her whole life and having hundreds and thousand of seizures. It affects her physically. So she does rely on her wheelchair. It’s her comfort zone; she’ll always want to go to it. On a couple of occasions recently, we’ve ditched the wheelchair and walked into the neurologists office. It’s not a miraculous—‘Oh my goodness, she can walk!’ But it’s a ‘Look at this, she’s not as fatigued as she was.’”

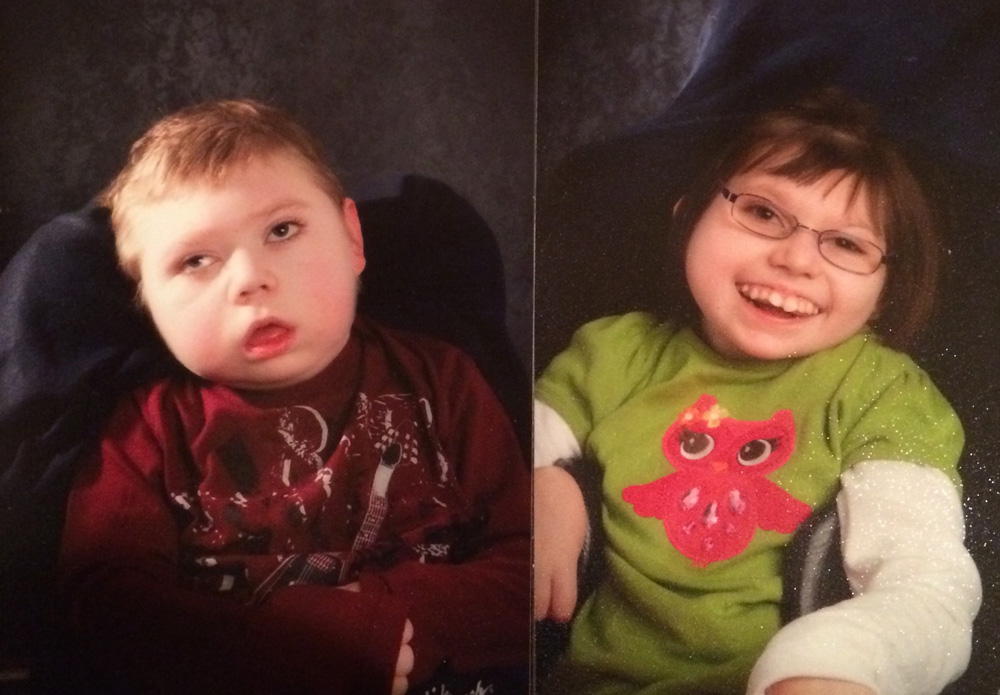

Caden Ryszka and Taylor Ryszka

Daniel Ryszka, a pharmacist in a local hospital, was an outspoken advocate for the program before its arrival, and he hasn’t been disappointed by its effects. Both his nine-year-old son Caden and his 15-year-old daughter Taylor suffer from severe seizure disorders. Taylor would suffer three to five tonic-clonic (formerly dubbed gran mal) seizures nightly, which were marked by an onset of screaming followed by minutes of convulsions. Some three months into the treatment, Ryszka could barely believe it himself when he spoke with The Public,that Taylor had gone three weeks without a seizure. “She’s happier, she’s more focused,” he says. “We didn’t really tell the school she was on it, and we’re getting reports back from the school. She’s definitely more alert, she’s making better, appropriate choices, and she seems to be responding very well to this.”

Before beginning Caden on a dosage regimen, a baseline EEG revealed that he was in a near constant state of seizure. “The doctor came back and said, ‘his brain is highly active, it’s like he’s in a constant state of seizure. They just don’t stop. So I can’t even count how many seizures he has. He’s always in one,’” Ryszka recounted. “This was on Tuesday. I started him on Saturday. He was seizing in the morning, his eyes were shimmering. Within 30 minutes, they stopped. He’s been spectacular since he’s on it. But again, it’s only been two weeks. We’re at the starting dose. I’m planning on taking him off the other pharmaceutical product at some point, but I want to make sure I can maintain him for a longer period of time. The product seems to be really working.” (Ryszka had a hard time putting into words what it felt like to look into his son’s eyes, almost as if for the first time.)

Kelly shares Ryszka’s goal, of weaning Mariah off pharmaceuticals for good. She wonders what the true toll is that the drugs have taken on her daughter. “What have nearly 20 years of drugs—pharmaceuticals, heavy-hitting drugs—done do to her body, to her brain, to her immune system, to her bones, to her eyes?”

Similar stories were shared by the proprietor of a longtime North Buffalo head shop. Bob Colasanti at Terrapin Station has developed a small but loyal customer base for CBD oil in the past year since he’s been selling it. CBD oil users experience none of the euphoria that THC users experience, but Colasanti has heard from customers using it to treat seizures, migraines, and aches and pains, and the side effects of chemotherapy. “People who are not comfortable with pharmaceuticals and the pharmaceutical industry,” he says.

The Program

The state currently has approved 526 physicians (though the Department of Health don’t provide a directory of who they are) and 2,675 patients to administer and receive medical marijuana products from five approved companies, each of which has four “patient resource centers” spread scattershot across the state.

Kelly makes use of both of the local dispensaries operated by Bloomfield and Pharmacannis. The staff at both are compassionate, she says, and mindful of the program’s cost to patients, which ranges anywhere from $100 monthly to well over a $1,000, depending on an array of factors (dosage, amount, and delivery method). Health insurance, of course, doesn’t cover the costs. “It’s not cheap. We make sacrifices every single day to make sure she gets what she needs.”

But she doesn’t go to both dispensaries to catch up with her pharmacists, but because each offers different a product. The higher CBD medicine is available at one, the higher THC formula at the other, and both limit their menu options to liquid form.

The largest dilemma the coordinator of the Dent Cannabis Clinic is encountering with patients is having to refer them to the New York State Thruway. “Our local dispensaries haven’t received any new product types/ratios since opening, and we have to do what is best for our patients. We can’t just send them locally because it’s convenient if they don’t have the proper dosages available,” Amanda McFayden wrote in an email.

Responding to a survey of area lawmakers conducted by The Public, Buffalo Councilman David Rivera said he had heard of a parent who “was driving to Binghamton because the dispensary there provides greater number of products with better results for her epileptic child.” And that “parents” who need the medicine “are coming together to create carpools to drive four hours away.” Seven of the eight state lawmakers responding to the survey agreed that the medical marijuana program should be expanded, with an eighth—Chautauqua County Assemblyman Andrew Goodell—expressing a guarded optimism. State senators Timothy Kennedy, Patrick Gallivan, and Assembly members Sean Ryan, Crystal Peoples-Stokes, Angela Wozniak, Ray Walter, and Robin Schimminger were all in favor of the program’s expansion.

Program expansion is something close to Daniel Ryszka’s heart. He’s spent time locally and in Albany advocating for children and patients statewide, championing bills like the current one in committee in the state senate that would allow additional dispensaries to be opened.

Beyond expansion, some changes at the federal level will need to take place to move the drug away from its classification as a Schedule I narcotic. For starters, Mariah Kelly can’t bring the drug her neurologist recommends as a seizure “rescue med” to school with her and doctors at the Veterans Administration can’t touch it.

With only 2,675 patients registered, expanding might be a zero-sum game for the five companies. The list of 10 illness that qualify for the program would have to be increased, and patients would need to have better access to doctors willing to participate with the program.

At the center of the local movement to treat patients with medical marijuana is Amherst’s Dent Neurologic Institute, a large practice near the I-90/I-290 interchange that makes it 30 minutes away from both Lewiston and East Aurora. Its medical director, Laszlo Mechtler, was among the first cohort of doctors statewide to participate in the program.

Speaking with The Public in January, Mechtler expressed he saw a moral imperative in getting involved with medical marijuana. “I firmly believe that if a physician acts in a compassionate way and doesn’t make a business out of this, then the physicians have every right to prescribe medications to relieve the suffering of their patients,” he said. “After doing this 25 years, it does get tiring to see people suffer and you can’t cure.”

McFayden said Dent has seen multiple stories like the ones told by Ryszka and Kelly. “We have a little over 100 patients certified with a variety of New York State-indicated conditions that are seeing relief from their pain, nausea, and are having days free or lessened from seizures,” she wrote in an email. “It’s truly been remarkable to see these patients back during their follow-ups to listen to and see their results.

“We do have patients receiving [medical marijuana] that have been able to begin weaning off of some of their preexisting medications, but that is done along side their physicians to make sure that is the best decision for their care.”

This article was first published on the Public on April 20.