Nonprofits pay a “pretty penny” for a spot in a community on the rebound

For the past two years, Glenn Martin has run his Harlem-based organization, JustLeadershipUSA, from coffee shops or anywhere else he can find to get his work done. Since founding the group, which is dedicated to halving the number of Americans in prison by 2030, he has hired several former prisoners as part of his staff of 13. He said it was critical to be based in Harlem, where New York City Department of Correction figures show that residents are disproportionately incarcerated compared with the rest of the city.

When he spoke to New York Nonprofit Media in June, Martin said he expected his new storefront on Lexington Avenue near East 118th Street to be ready over the summer; four other locations fell through because landlords broke off talks when competing tenants made better offers. He needed a security deposit equal to one year’s rent, which, along with other upfront costs, amounted to $80,000 to secure the space. It cost a “pretty penny,” he said, but he wanted to have an inviting storefront where clients felt comfortable.

“It’s great to be in Harlem,” Martin said, “but we’re going to pay for it for the next 10 years.”

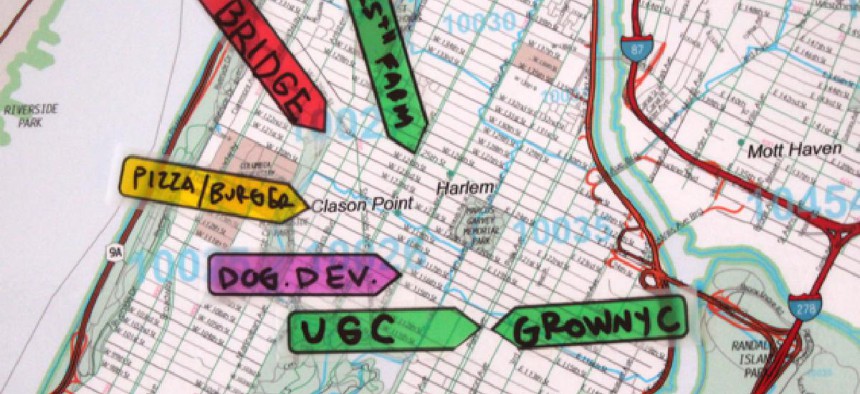

While the shortage of affordable housing and other effects of gentrification weigh heavily on low-income residents of Harlem, JustLeadership and other Harlem-based nonprofits are facing their own related challenges: rising operating costs, a lack of space to expand existing operations, or, for others, a struggle to find a suitable location in the community in the first place. While prices generally remain lower in Harlem than in Midtown and lower Manhattan, some organizations seeking to be closer to the people they serve are having a hard time competing with commercial tenants.

For other nonprofits in the city, these trends have actually helped. Price increases in parts of Manhattan – such as Gramercy and Flatiron, where technology start-ups have contributed to growing demand for space – paved the way for established charities to capitalize on the changing market. The Mission Society, Community Service Society and Children’s Aid Society in 2014 sold their stakes in the United Charities Building on Park Avenue South for a reported $128 million and used the proceeds to move elsewhere.

The Mission Society, a two-century-old social services agency which had been located in the building since 1892, moved to its Minisink Townhouse, a community center it built in 1965, on Malcolm X Boulevard off 143rd Street. The organization’s president, Elsie McCabe Thompson, said it “made perfect sense” to move closer to its constituents in Harlem and the South Bronx. “If you live among the people you serve, then you have a daily reminder of why you do what you do,” she said.

While owning the building helps resist market pressures, Thompson said other groups find it hard to move to Harlem. “I know there are a number who would like to be uptown, but there is limited office space uptown, particularly large swaths of office space,” she said. Those who can operate out of storefronts have more opportunities, she added, but they also compete with commercial ventures.

Thompson said she would love to have more nonprofit space in her neighborhood, but finding it is a challenge. “I know a number of other nonprofits who I never would have imagined leaving their preferred Midtown or lower locations who are looking to headquarter in the South Bronx because of affordability,” she added.

Residential rents in Central Harlem and East Harlem increased by 53.2 percent and 40.3 percent, respectively, between 1990 and 2014, according to an annual NYU Furman Center report released in May. The de Blasio administration has made it a priority to build or preserve more affordable housing for residents, but Thompson said smaller nonprofits could use help, “because not everyone in the nonprofit sector is a large hospital or large educational institution that have major endowments.”

By contrast, when the Community Service Society left the United Charities Building, it bought an office condo in a Midtown Manhattan building shared by Gov. Andrew Cuomo and other nonprofit tenants because it was a central location for its workers’ commutes and offered easy access to all five boroughs it serves.

CSS President and CEO David R. Jones said many nonprofits, particularly non-arts organizations in poor neighborhoods, are already financially strapped. As a neighborhood improves, a nonprofit’s financial challenges can grow: “If I’m sitting there providing HIV services or services to the formerly incarcerated in a gentrified neighborhood, suddenly the political and the local support for that begins to wither,” he said.

Jones said market forces could result in more nonprofit failures or consolidations without government intervention. “As this price escalation goes up, in addition to providing low- and moderate-income for people to live, you’re also probably going to have to provide some incentives to provide a boost for not-for-profits,” he said.

For his part, Martin said the city should provide more resources for smaller nonprofits, such as loans to cover moving or security costs.

City government does offer some programs and services to help nonprofits. The city’s Economic Development Corporation provides incubators and workspaces for such organizations. In Harlem, the Oberia D. Dempsey Multi-Service Center, run by a local nonprofit on behalf of the Human Resources Administration, houses roughly two dozen programs offered by providers such as City Health Works, Graham Windham and Harlem Grown.

Others point to the neighborhood’s poor transportation and limited supply of office space. Suzanne Sunshine, the head of S. Sunshine & Associates, a real estate firm whose portfolio includes nonprofits, said many organizations have gravitated toward Lower Manhattan, which has better transportation access. While prices in Harlem can be as low as $36 per square foot, versus $51 downtown, she said, few clients have expressed an interest in moving there. Only one of the 10 nonprofit deals she has completed over the past two years was in Harlem. “Right now, there are no nonprofit neighborhoods in Manhattan,” she said. “Harlem does make sense, but there’s just not a lot of product there yet.”

David Nocenti, the executive director of Union Settlement, which runs community spaces and facilities for early education, seniors and mental health services at 15 locations around East Harlem, said he encountered a “shrinkage” of available space throughout the neighborhood due to the rising costs. At one center on East 122nd Street, the landlord announced plans to “substantially” raise the rent by double digits after June. While the city’s Administration for Children’s Services, which fully funds the program, is picking up the increase, he said, a non-governmental grant may have been less flexible.

But city government also poses an additional challenge for nonprofits like Union Settlement. All but two of the organization’s locations are in spaces owned by the New York City Housing Authority. According to the agency’s NextGeneration plan, a blueprint on shoring up the ailing public housing provider, more than 20 percent of NYCHA’s community spaces are vacant. In order to generate more revenue and ensure that tenants’ rents are covering NYCHA’s operating costs, it plans to “aggressively lease its retail space portfolio” and begin “re-examining its current lease arrangements, including utility cost pass-throughs and rental rates” for community-based organizations. This strategy favors commercial tenants and makes community and retail spaces harder for nonprofits to get because they often don’t have enough capital to fix up spaces in disrepair, Nocenti said. The situation mirrors the challenges faced by residents and “mom-and-pop” stores, he added.

“It’s a microcosm of what’s happening all across the neighborhood, in that space is going to become at some point unaffordable for nonprofits, and that’s why I’m very concerned about NYCHA taking community space offline,” he said. “Because that’s really going to be the last space that’s available. And if they rent it out to a laundromat or a restaurant or a nail salon or something like that, then families aren’t going to get other services they need.”

NYCHA spokeswoman Zodet Negron said that the agency has leased more than 27,000 square feet of empty community space to community-based organizations since May 2015, including the Dominican Women’s Development Center, Jacob Riis Neighborhood Settlement and a branch of the New York Public Library. It has also stepped up efforts to start collecting enough money to sustain rent and utility costs for some 160 stores and 415 organizations operating out of its retail and community spaces.

“To that end, we launched a comprehensive leasing strategy to maximize the use of our ground floor spaces, bring online spaces that have been offline for years, decrease subsidies to tenants in order to lower the authority’s operating costs, generate rental revenue – and, most importantly, provide strong services for residents,“ she said.

Regardless of the struggles reported by some organizations, Mark Goldsmith, the co-founder and president of Getting Out and Staying Out, another prisoner re-entry organization, said groups can still find storefront space in the neighborhood. He said he likes the convenient access for clients and his staff at his East 116th Street location. “You couldn’t get me out of here for love nor money,” he said.

After former President Bill Clinton moved his offices to 125th Street in 2001, Goldsmith tried to find an affordable space in that corridor, too, but failed. Tired of high rates and struggling to find a landlord who would take on a tenant with a number of former inmates as clients, Goldsmith knocked on doors and inquired about vacant storefronts until he found a location. He negotiated an expansion with his landlord two years ago, doubling the local capacity to serve 500 people per year.

“If you do your homework and go the way I did, building by building, literally knocking on doors to find the right spot, and I did it, and I’m still here,” Goldsmith said, arguing that gentrification is the least of the problems facing the struggling nonprofit sector.

Martin of JustLeadershipUSA echoed the sentiment about the importance of staying uptown. He turned down a spot on Maiden Lane in Downtown Manhattan in favor of a spot in Harlem, where he has served on the local community board and become a more visible criminal justice reform spokesman.

“We could have went and gotten a turn-key office in Downtown Manhattan where people have to go past a tremendous amount of security to get in and so on,” he said. “And that did not fit the brand, it didn’t fit our mission.”

This story previously ran in City & State in June.