Nonprofits continue efforts to save New York state support for Close to Home program

Courtesy photo

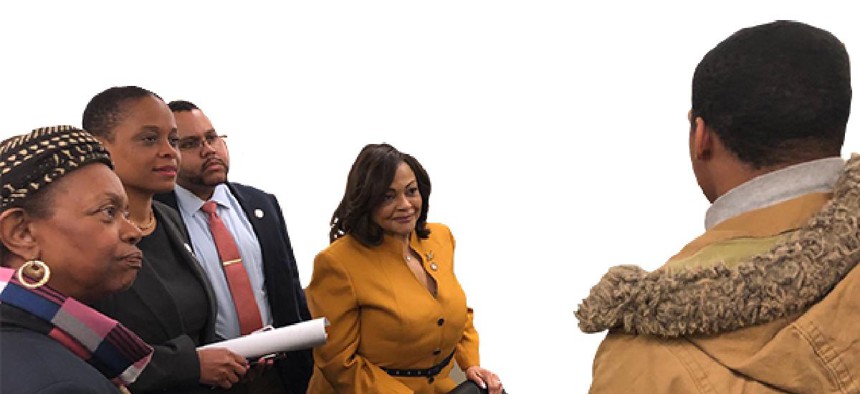

A 14-year-old former juvenile offender named Justin was well positioned in a New York State Capitol hallway as a group of lawmakers emerged from a backroom meeting just after high noon on Monday, March 5.

There was State Senator Velmanette Montgomery, and counterparts from the Assembly: Tremaine Wright, Victor Pichardo and Inez Dickens. And these legislators were about to come across a group of a dozen juvenile justice advocates who were prepared to lobby as hard as they could to whomever was willing to hear about why the Close to Home program needed to be saved. was in peril.

“Good Shepherd Services!” said Montgomery.

She had recognized a representative of the New York City nonprofit in the hallway and before she knew it, Justin had been brought forward to tell the Democratic lawmakers how Close to Home had transformed him from a juvenile offender at risk of recidivism into the thriving teenage boy whose height had him hovering above them all and whose words evoked statements of support from the legislators, Annie Minguez, a representative of Good Shepherd Services who was among the group in the hallway, told New York Nonprofit Media.

"When you’re able to bring young people to tell their story it is one of the most impactful ways to make members listen,” She said in a telephone interview. “(Justin) learned as being part of Close to Home that his mistakes don’t define him and he could leave this program and start new.”

Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s proposed budget for the upcoming year would effectively cut about $40 million from the program – and likely end it. To keep that from happening, Close to Home agencies and their supporters are engaged in an increasingly urgent effort to take cuts to the program off the table in the ongoing budgetary tug of war between Cuomo and New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio, advocates told NYN Media.

They’ve met with dozens of lawmakers of both parties, lobbied the Governor’s Office, staged rallies and advocated alongside the New York City Administration for Children’s Services – in the hopes of convincing Cuomo to backtrack on effectively shuttering a program he was instrumental in establishing.

Cuomo’s representatives did not respond to a request for comment by press time. But they have said before that state funding for the program was only intended for a five-year pilot program and that a $500 million boost in overall state funding to New York City could help cover the proposed cut to Close to Home – if the city got its fiscal act together and “finally” looked for efficiencies within its budget, one spokesperson told City Limits. ACS Commissioner Hansell responded to that argument during a recent NYN Media Insights podcast by saying the state also has a reserve, “and the governor is proposing to continue it.”

Youth advocates say that they remain cautiously optimistic that they can keep the program from becoming collateral damage in the larger conflict between the city and the state over topics like taxes, MTA projects and NYCHA repairs and how much the city and state are respectively responsible for each. Another Cuomo proposal would establish a cap on state funding to child welfare – substantiating fears of that divide becoming legislative reality, according to Jeremy Kohomban, executive director of The Children’s Village, a Close to Home provider.

"My best hope is indeed that this is a negotiating position,” Kohomban said in a telephone interview. "It would take a lot more than this to convince me that Gov. Cuomo doesn’t care.”

In the meantime, advocates are hedging their bets and pressuring their legislators. Raul Marrero, a coordinator at Sheltering Arms Children and Family Services was also in Albany with a story of personal redemption to tell.

He wasn’t as lucky as teens like Justin who had the opportunity to go through a Close to Home program. Raul was born into a poor family and spent the years from age two to 21 in foster care.

“Far from exceptional, Raul’s story reflects a struggle that is all too familiar to black and Latino boys growing up in poverty,” reads a biography written by Sheltering Arms.

He was sexually and physically abused. Aunts mistreated him and his brothers. They soon had to get creative to find food. Raul began to rob people after an aunt spent his foster care money on cocaine. Before long he came to the attention of juvenile justice authorities. A diversion program did not work and Raul eventually found himself on Rikers Island at age 16, and later solitary confinement.

“Raul starts every part of his story with ‘Imagine …’ before describing some other-worldly scenario prisoners endured. He knows that most readers must plumb the depths of their imaginations to picture what he has gone through.”

When he finally was free in 2003, a free soda from a Brooklyn bodega inspired a new feeling within him. It’s a feeling of hope he shares in his work with foster youth, a lesson made easier to learn through the Close to Home program, he says.

And if sometime between now and April 1 – either on a nonprofit lobbying day or otherwise – Raul found himself with a chance to speak face to face with Cuomo, he has already thought about what he would say during such an encounter.

“I know there is a lot of in-house fighting, but you’ve seen the importance of Raise the Age. You’ve seen the importance of closing prisons,” Raul said during a phone interview. "We need to provide these kids with the tools they need.”