Leader to Leader: Herb Sturz

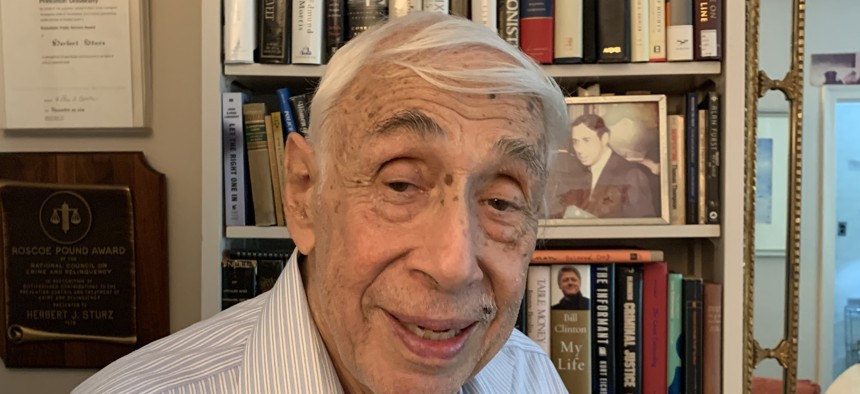

Herb Sturz, president of Democracy Alliance. Submitted

Gara LaMarche, the president of Democracy Alliance, calls Herb Sturz “the good Robert Moses.”

Since the 1960s, as detailed in Sam Roberts’ biography “A Kind of Genius,” Herb has helped create a broad array of nonprofit organizations in New York, including the Vera Institute of Justice, Safe Horizon, ExpandED Schools, and the Center for NYC Neighborhoods.

While his biggest impact has been felt within the nonprofit sector, Herb’s idiosyncratic career has also featured time in government (including serving as deputy mayor under Ed Koch), journalism (as a member of The New York Times’ editorial board), and philanthropy (for the Open Society Foundations).

The comparison to Robert Moses is apt: Herb has been one of New York City’s most important behind-the-scenes power brokers for six decades. Unlike Moses, Herb’s career has been defined not by the enemies he has made but by the friends and allies he has cultivated – many of whom continue to occupy positions of influence throughout the New York City nonprofit sector.

I recently talked to Herb over the phone. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Berman: Your original claim to fame was creating the Manhattan Bail Project, which sought to address the inequities of the bail process. That was 60 years ago. And here we are in 2020, and we're still talking about people being needlessly detained. I'm interested to hear how you reflect on this reality and whether you feel that bail reform is a story of failure, or success, or something in between.

Sturz: Obviously, I've thought about your question. And I do think, broadly, the story is one of success. Bail was barely out there as a serious subject when I started. Am I satisfied with where things are? Of course not. But did we make some real breakthroughs related to law and poverty? We certainly helped change the face of bail in this country. Today, massively more people get released before trial than was the case back then. The work still goes on, with bail funds all over the country now and the new bail legislation. It's been, broadly, I think, a success. I don't say it was my success altogether. Of course not. But I played an early key role in making it happen.

Berman: I'm curious about that moment back in the early 1960s when you helped convince then-Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy to throw the weight of the Justice Department behind bail reform.

Sturz: I got to Robert Kennedy through a fellow named Dave Hackett, who was a classmate of his at Milton. My first meeting with Kennedy was kind of wonderful. It was in his small office at the Justice Department. His dog was around. And I remember he said he was very interested in what I was doing. But he said, "I want you to know you must work with other people on this." And before I could say, "Well, of course," David Hackett said, "Mr. Attorney General, there are no other people." I don't know if that was true entirely, but it was largely true. Anyway, we had this wonderful dinner, and it was followed by, very quickly, some Supreme Court opinions that referenced bail reform.

I was lucky. And I was opportunistic, going from one person to another. The Department of Justice ended up putting together a national conference on bail and criminal justice. It was really amazing that the department co-sponsored it with an infant nonprofit called the Vera Foundation. We ended up inviting representatives from every state in the nation to Washington. It was an ego trip for me. My friend Dan Freed wrote Robert Kennedy's speech, and I had a hand in writing the chief justice's speech.

Berman: How did you go from advancing the idea of bail reform to creating the Vera Institute of Justice?

Sturz: Well, Vera was initially formed in order to be a vehicle to develop The Bail Project. I actually used to go into the jail cells and interview accused people. And I learned about much more than just bail reform. And as I got into it, I saw people that were just beaten down by the system. And one experience and bit of knowledge led to another, and it led me to ask the question, "How can we institutionalize this work?"

I started by reaching out to Louis Schweitzer. He was kind of an original thinker and very much into the First Amendment. So I walked into his office and asked him for money. And he said yes. It was a very small amount of money, actually. And then we got our first real money from the Ford Foundation.

From our start focusing on bail, it just seemed natural to say, "Well, who are these people that are caught up in the system?” So I went down to the Bowery and kind of lived there for a week or so. I spent time walking the streets and talking to police and the skid-row derelicts. They could be arrested and rearrested up to three times a day. It smelled of vomit and sorrow. And that led to Project Renewal, which was initially known as the Manhattan Bowery Corporation. We created supportive housing for some of the sickest people on the Bowery. We created it on the third floor of the men's shelter at 8 E. Third St. I remember it to this day. And that was an example of a Vera project.

Berman: One of things that you did at Vera that I think was remarkable was your decision to spin off Vera projects. I’m not sure folks realize how many New York City nonprofits began life as Vera projects. I'm sure I'm not going to remember all of them off the top of my head, but in addition to Project Renewal, there’s CASES and CJA …

Sturz: Oh, I think there are about 30 to 35.

Berman: So I'm definitely not going to remember all of them. Anyway, that was a remarkable decision, to spin these projects off.

Sturz: I did it by instinct. Normally, you wouldn’t spin off these corporations. You would agglomerate. But I tried to spin off the strongest – those that had really good people and a strong financial footing. I wanted them to build their own names. Somehow I instinctively knew this was the right thing to do. I knew it would vitiate our ability to innovate if we got too big. Another part of it was that I did not want too much publicity. I knew we needed a little. But too much publicity, I thought, could kill us.

Berman: Why is that? Many nonprofits think the opposite – that their job is to get as much public attention as possible.

Sturz: Generally, if you put your ego up front too much, it comes back and it bites your rear. On the other hand, you have to build strength so you can keep doing more work. It's a subtle business. But, largely, you want the strength to come out of your accomplishments and giving other people credit. I think we put out, at Vera, only two or three press releases in my 17 years.

The Midtown Community Court, I think, is an example of what I’m talking about. The Midtown Community Court grew out of all of my experience with pretrial justice. It was a real hard project to get going. Manhattan DA Bob Morgenthau and his top assistant hated it. They said that they could run a community court at 100 Centre St. (Manhattan’s centralized courthouse), which of course is a contradiction in terms. To get Midtown done, you needed a show of power. But you needed to show it quietly and be very careful about saving the face of the people who you ultimately needed to work with.

Berman: You’ve been a role model for many nonprofit leaders over the years, including me. Did you have any role models? Was there anyone that you took cues from?

Sturz: I don't think that I was consciously trying to model myself after any person. But when I was in my 20s, the guy who really affected me as much as anyone was John Steinbeck. I sent Steinbeck this paper I wrote on “The Grapes of Wrath.” And the fact that he responded to me, and he poured his heart out in this handwritten letter, three and a half pages, that gave me a confidence. I saw it as amazing generosity to somebody he knew nothing about.

But in general, I don't really think I've had a particular model in my work. I've thought of myself as just kind of following information, following facts, following experience, one to the next, one to the next, thinking, where can this go? What are the implications?

Berman: One of my favorite parts of your resume is that you were a novelist.

Sturz: I wouldn't say that. I did write a novel with Elizabeth, my first wife. We were living in a little village in Spain. We had just met. I couldn't have been more than 23. But I got to know the people I was living around, all the fishermen, and the difficulties of their life, and the extraordinary poverty. I've always believed in the inductive rather than the deductive. My experience, my career, is going from the immediate and expanding outward. I believe in the experiential, in building on the knowledge that you've acquired largely through experience.

Berman: I want to pivot and talk a little bit about Rikers Island, because I think that’s a good example of one of your best qualities, which is your perseverance. When did the idea of closing the jails on Rikers Island first cross your radar?

Sturz: It came up when I was part of the Koch administration. It may have been percolating before, while I was still at Vera. But it certainly came up strongly when I worked for Koch, both in my position as deputy mayor and as chairman of the Planning Commission. The first idea was to sell Rikers to the state. And we came real close to pulling it off.

Berman: Where did the idea founder?

Sturz: It was undone by some people in the Koch administration. There were budget concerns. And there were, obviously, concerns in the community. It was a big disappointment.

Berman: So fast-forward to a few years ago and the Lippman commission. How did you advance that idea?

Sturz: I was then at Open Society. I was working with Peter Samuels. He was volunteering his time. I had the idea of getting (former state Chief Judge) Jonathan Lippman to be chairman of a commission that would look at closing Rikers. I felt that we really needed an outside force to come in and push the idea forward. We got (then-City Council Speaker) Melissa Mark-Viverito to authorize the commission. And we gave a lot of thought to who should go on it. I remember calling Darren Walker (of the Ford Foundation) and saying, "Darren, we need you on this.” There were a few people that were really crucial to this. He was one of them. The Center for Court Innovation was also crucial. The Center did all the real lifting. I don't know whether it would've been pulled off without the work of the Center. And of course Judge Lippman himself was crucial. He wasn't just a former chief judge, he was – and is – a very smart and aggressive politician. I don’t believe that the city would have committed to closing Rikers Island without the Lippman commission.

Berman: You have always had a propensity for optimism. We're obviously in the midst of a time of real change and instability. I'm wondering how you feel about this current moment. Do you still feel optimistic?

Sturz: I feel optimistic. I also feel pessimistic.

Berman: So what makes you optimistic and what makes you pessimistic?

Sturz: Probably the same things that make you optimistic and pessimistic. Hey, we're alive. We've got to keep doing things. You’ve just got to keep going until you can't. I keep thinking back to Voltaire, to Candide. Dr. Pangloss is very optimistic and thinks this is "the best of all possible worlds." If I recall correctly, Candide says, "Yes, but let us cultivate our garden." You’ve just got to keep at it.

NEXT STORY: New York’s census response continues to lag