Native American nonprofit aims to boost community health by teaching Lakota language

Illustration by Zach Williams/ NYN Media

In a small room in the basement of New York University, Aru Apaza sits with a group of a dozen others and gushes about American Indian Community House – a nonprofit that has become a home away from home for her.

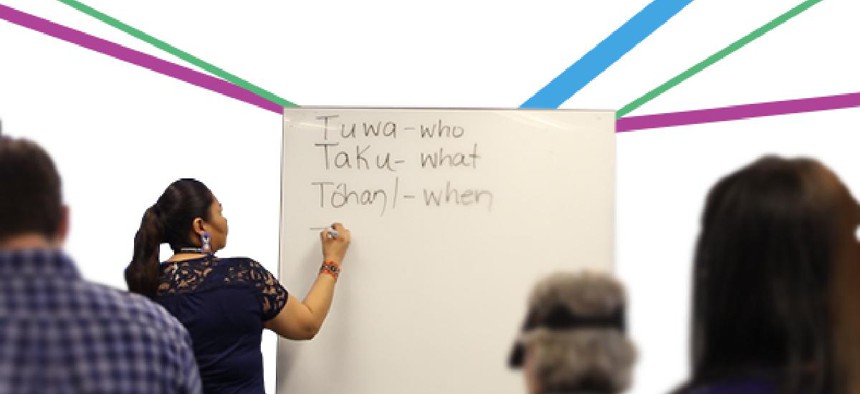

She is speaking to a group made up of staff and volunteers from AICH, the Language Conservancy and New York University’s Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies. They have met to kick off New York City’s first Lakota Language Weekend – two days dedicated to improving community health and overall well-being through the speaking and learning of Lakota.

“It is good medicine to hear people hearing the language,” said Apaza.

It's all part of an ongoing work at the lower Manhattan-based nonprofit, which was founded in 1969 by Native American volunteers to support their community and create intercultural understanding at a time when indigenous communities across the U.S were reasserting their identity.

Programs include "well-briety circles" for those looking to recover from addictions, mental health services and assistance with finding affordable health care providers. The organization, led by Ben Geboe, has become one of the oldest urban Native American health programs in the United States. By hosting a Lakota Language Weekend, AICH is adding another tool to its interventions for improving well-being.

A 2016 study suggests that efforts to keep a language alive translate into health-related benefits for Native Americans. Language use generates a strong sense of connectedness to the community and cultural history. And an increased interest in the culture goes hand in hand with an increased desire to improve community health.

“I needed it for my own identity as a Lakota person,” said Alex Firethunder, an instructor during the Lakota Language Weekend. “Spiritually, emotionally, I felt like I wasn’t meeting my full potential as a Lakota person."

Firethunder grew up in Upstate New York but left home to study on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. During his childhood he spent every summer in South Dakota and dreamed of living on the reservation to be with his people and learn Lakota. His mother is a Lakota speaker but chose not to teach it to her children. Now Firethunder is the Lakota language and cultural coordinator at the Lakota Waldorf School on that reservation.

The Endangered Language Project categorizes the Lakota language as an extremely endangered one. Since the 1700s, many speakers of Native American languages were forced or pressured by white settlers to only speak English, which has played a role in the decreasing numbers. As of 2016 there were about 2,000 native Lakota speakers left with the majority being over the age of 65. To help address this, there have been six Lakota Language Weekends in various cities since it began in 2016. AICH reached out to the Language Conservancy’s director of communications to explore hosting the event in New York City for the first time.

The health status of Native Americans is such that every possible beneficial intervention is appreciated, research shows. According to the Indian Health Service, Native Americans suffer some of the poorest health outcomes of any other racial group in the United States. Native Americans and Alaska Natives have a life expectancy of 73 years, four years less than the national average.

According to the National Congress of American Indians, the suicide rate among Native Americans is 62 percent higher than in the non-Native American population. Suicide is also the second leading cause of death for Native youth between the ages of 18-24.

“I mean everybody knows someone that has done it. It has almost become normalized,” said Renelle White Buffalo, another Lakota language instructor who traveled from South Dakota to participate in the weekend.

Firethunder credits learning Lakota as a step towards creating better outcomes for himself and his family. He wanted the ability to pass on his ancestral language to his own children and he has already seen first hand the physical and mental health benefits to his community:

“Most of those people are sober, most are further in their education, they worry about their well being and they are pushing to be better,” said Firethunder.

NEXT STORY: New York lawmakers divided on Rexit