Opinion

Opinion: The cost of a workplace disaster

This Labor Day, New York must bring justice to fallen workers

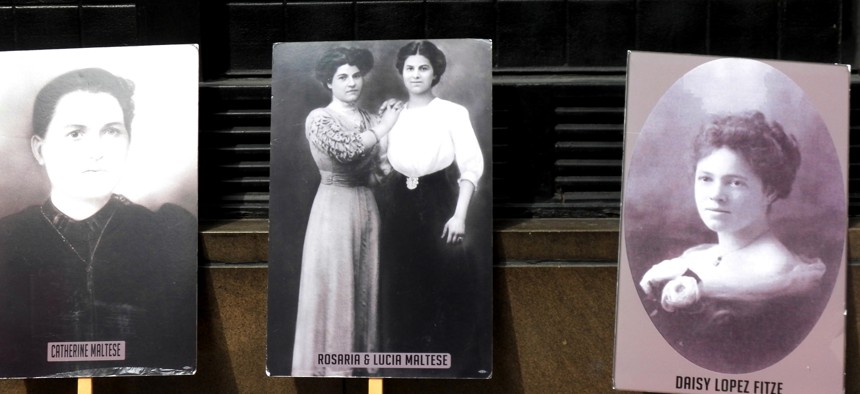

Images of some of the 150 workers who perished in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire on display in Greenwich Village where the blaze happened. (Photo by Mark Apollo/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images)

One of the deadliest workplace disasters of the industrial era, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, killed 150 workers in 1911 in Greenwich Village. Most of the victims were immigrant women and girls, some as young as 14. This Labor Day, New Yorkers should appreciate the hard- fought history of the labor movement while recognizing that the work is far from over, and that in many ways, it’s more dangerous than ever before to be a worker here.

Construction-related deaths in the city are at a 10-year high, with fatalities up 9% in 2021, to 12.1 deaths per 100,000 workers. Latino construction workers accounted for 25% of the deaths – up from 18% in 2020.

Fortunately, there is a bill in New York that will bring justice to fallen workers and help deter negligence on worksites, and beyond. At the New York Committee for Occupational Safety & Health, we know that workplace injuries, illnesses and deaths are preventable.

The Legislature also recognizes this, and that’s why the Grieving Families Act, a bill that would allow victims’ families to recover for emotional grief and anguish in wrongful death cases, has passed – twice – with overwhelming bipartisan support in both chambers. A coalition of advocates including the NAACP, AARP and New Yorkers Against Gun Violence, support the Act.

After the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, more than 20,000 workers from 500 factories staged a walkout. As a result, many factory owners negotiated with workers for fairer contracts, shorter work weeks and paid overtime. Organized labor achievements, such as the eight-hour workday, sick leave and child labor laws, all exist to keep the vulnerable safe. These victories are why we celebrate Labor Day.

But, with over 20 construction-related fatalities on the books for the last recorded year, it is hard to feel celebratory. New York leads the nation in construction site deaths.

Mauricio Sánchez was one of those preventable tragedies. Sánchez was the third worker to die at a single work site in the Bronx in less than three years, when he plummeted 75 feet to the ground at 20 Bruckner Boulevard in 2021. Other workers at the deadly working on the building under construction reported earning as little as $120 a day for performing hazardous labor at the non-union site.

Such incidents are one reason why this Labor Day, our governor, Kathy Hochul, should use her authority to sign the Grieving Families Act, and help honor fallen workers like Sánchez. The Grieving Families Act would amend the state’s backward, 1847 tort laws. It will bring greater equity to a law that has, for nearly 200 years, discounted the lives of the workers who built our great city.

New York City is the city of dreams. But embedded in those dreams is a nightmare: one that has for hundreds of years abandoned the weak in their greatest moments of need.

The appalling loss of life at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory was possible because the laws at the time, and lax enforcement thereof, allowed management to keep the exits locked to prevent theft and “stealing time,” as well as to keep out union organizers and prevent spontaneous walkouts. In the aftermath of that infamous disaster, the proprietors collected their insurance and reopened at a new address. The families of the victims were initially offered one week’s pay as compensation for the loss of their loved ones, and three years later, the owners were ordered by a court to pay damages of $75 each to 23 families of victims who had sued.

In the 112 years since those young women lost their lives, we have come a long way to address the multitude of workplace violations that led to their deaths. But 20 Bruckner Boulevard shows us that we have not come far enough. Horrifically, the laws in place in 1914 – the year the owners of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory paid out a measly $1,725, which is the inflation- adjusted equivalent of $52,731 today, in total, for the 150 lives lost in the fire – are the same laws in place today.

The Grieving Families Act not only brings justice to laborers; it also provides a financial deterrent to employers who see the lives of low-income workers, who are often immigrants, as disposable. Last year, Gov. Hochul struck the bill down, in a bid for more time to get the language of the legislation right.

It is my hope that this Labor Day, our governor remembers the fallen workers who died in pursuit of the American dream and signs the Grieving Families Act. New York is the heart of the labor movement, and our state must lead the crusade to protect workers.

It also must restore hope to the relatives of those who lost their lives chasing this dream. The Grieving Families Act will honor the fallen, and bring justice to the living.

Charlene Obernauer is executive director of the New York Committee for Occupational Safety & Health,

NEXT STORY: Opinion: Looking at Women’s Equality Day from behind bars